Feb 15, 2026

From PEO to PAE: Why Operating Model Matters More Than Org Chart

The shift from Program Executive Officer (PEO) to Portfolio Acquisition Executive (PAE) is often framed as a structural change. In reality, it’s a shift in how the Department of War (DoW) expects acquisition organizations to work.

While organizational charts change who reports to whom, operating models determine how decisions get made, what behaviors are rewarded, and how tradeoffs are resolved under pressure. For newly appointed PAEs, that distinction is not academic – it’s decisive.

PAEs effectively get one real chance to stand up their organizations. Early choices about decision rights, incentives, and metrics harden quickly into enduring culture and process. When those elements are misaligned, even sustained leadership attention will struggle to fully offset their effects.

Why the PEO playbook breaks at the portfolio level

PEOs are trained and rewarded to optimize programs. In many ways, that mindset has served the DoW well. Managing cost, schedule, performance, and risk at the program level is essential to delivering capability.

But portfolio leadership introduces a different problem set and opportunity.

PAEs are no longer responsible for making each program as strong as possible in isolation. They are responsible for ensuring the portfolio as a whole delivers operational capability faster, at scale, and in a way that strengthens the industrial base.

That requires:

making tradeoffs across programs, not just within them

reallocating resources dynamically

accepting uneven outcomes in pursuit of portfolio-level advantage

A portfolio can fail even when every program is “well run.” That reality demands a different operating model.

What the CEO paradigm really means

DoW leadership has used the analogy that PAEs should operate with the mindset of CEOs. The analogy is useful, but incomplete if interpreted as a call for personal leadership excellence alone.

CEOs don’t succeed because they make every decision themselves. They succeed because they design organizations where:

decision rights are clear and placed at the right level

people at all levels are empowered to make decisions, and accountable for them

incentives reward the outcomes the enterprise actually wants

tradeoffs are explicit, and made quickly and transparently

Just as important, they build organizations that continue to function when leadership changes.

In DoW, leadership rotation is a fact of life. Portfolios persist. An operating model that only works with the “right” PAE in place is a fragile one.

The DoW context: why operating models matter now

The move toward portfolio acquisition is not abstract reform. It’s a response to concrete DoW imperatives, and, if executed well, a genuine opportunity to improve how capability is delivered to the warfighter:

Speed: Capability delivered late is capability denied to the warfighter.

Operational outcomes: Success is measured in fielded capability, not completed process.

Industrial base health: Industry needs predictable demand signals to invest and scale.

Private capital: Non-traditional vendors and investors require credible pathways to transition.

Market fluency: Acquisition leaders are now expected to understand how commercial markets, capital, and incentives actually work.

PAEs sit at the intersection of these pressures. Org charts don’t resolve them. Good operating models do.

The levers PAEs must align

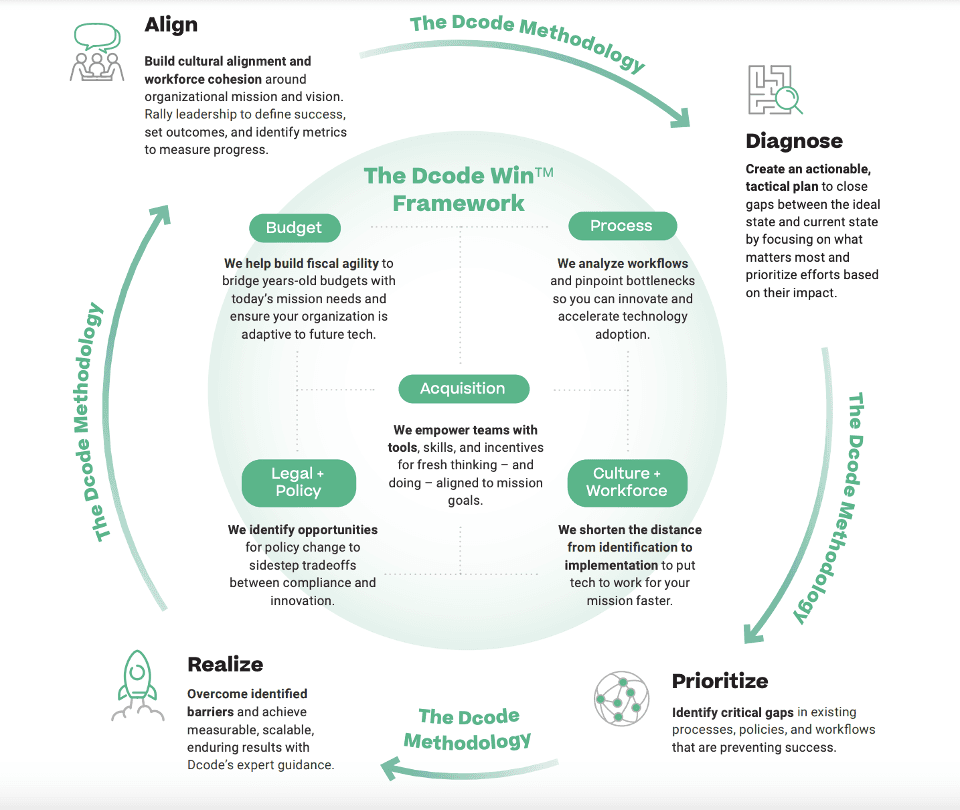

In the DoW context, operating models aren’t defined by decision rights, incentives, and tradeoffs in isolation. They’re defined by how these things are applied to align and reinforce a small number of system-level levers found in federal government practice.

Across DoW acquisition organizations, five levers consistently determine whether portfolios move at speed or stall:

Budget

Process

Acquisition

Legal and policy

Culture and workforce

These levers exist in every organization today. The performance difference isn’t in their presence but in their alignment around outcome and purpose.

Pulling one lever in isolation rarely works. Budget flexibility without structured acquisition pathways creates oversight concerns. Faster processes without policy clarity create risk. Culture change without incentive change produces compliance theater.

Decision rights, incentives, and tradeoffs: where portfolios live or die

Operating models succeed or fail based on three fundamentals.

Decision rights:

Who has the authority to make portfolio-level calls? Where can resources be shifted? Who can accept risk in exchange for speed? If these rights are unclear, decisions default upward – and speed evaporates.

Incentives:

People respond to what they’re measured and rewarded on, not what strategy documents say. If incentives favor compliance with process over delivery of capability, that’s exactly what the organization will get, regardless of leadership intent.

Tradeoffs:

Every portfolio decision involves balancing cost, schedule, performance, scale, and integration. The question is not whether tradeoffs will be made, but whether they’re made deliberately and consistently – versus implicitly and without intent.

This is where operating model design becomes real.

Metrics as the enforcement mechanism

Metrics are how incentives are made tangible. The most effective PAEs will move beyond program-by-program reporting and establish cross-functional metrics tied to capability delivery, such as:

time from problem definition to fielded capability

throughput time across requirements, contracting, testing, and transition

how consistently commercial solutions move from pilot to production

whether portfolio resources are being reallocated based on real signal, not sunk cost

These measures cut across silos. They force conversations org charts avoid. And they make tradeoffs visible.

Just as importantly, they send a signal outside the Department. For industry and private capital, predictable pathways and credible metrics, because they lower perceived risk, are what turn interest into investment.

What successful PAEs lock in early

The PAEs who succeed will focus their first 90-180 days not on reorganization, but on institutionalizing:

A user-centered understanding of the capability the PAE needs to supply

Clear decision rights at the portfolio level

Incentives aligned to speed, learning, and delivery, not activity

Explicit rules for making and revisiting tradeoffs

Metrics that reflect capability outcomes, not process compliance

Alignment across budget, acquisition, policy, process, and workforce levers

A generational opportunity

The transition from PEO to PAE is not just a new title. It’s a chance to redesign how acquisition organizations make decisions, allocate resources, and deliver capability at speed.

Those who focus on structure will get reorganization. Those who focus on the operating model will get results.

And in today’s DoW environment, results are what ultimately matter.

The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.